Intro

Hi, today I want to talk about video game randomization, and specifically the algorithm I designed for my Project Base randomizer. I also have a design for a new algorithm that I’ll get into a little bit as well.

What is a randomizer?

A randomizer for a video game is a program that takes as input a game, and outputs either a game or patch to apply to a game, in which the items, or another variable, have been randomized in terms of their location or another attribute. That is to say, generally speaking a randomizer changes what items appear at what locations in a game. For some games, items can’t be acquired out of a specific order, or the items do not majorly impact the game progression, and so it may be another aspect of the game that is randomized. For example you could randomize the level order, or the level design itself, or even the effects of different items. Most randomizers are based on games where items act as keys to progression locks, but just because a game isn’t a metroidvania doesn’t mean it can’t be randomized for a fresh new experience. Speaking of which, that’s the main draw of randomizers. They provide a new way to experience a game that you enjoy. The type of randomizer I will be talking about is specifically the kind that uses items as keys to locks, where the locks are usually level design, or enemies/bosses that require items, etc.

How does a randomizer work?

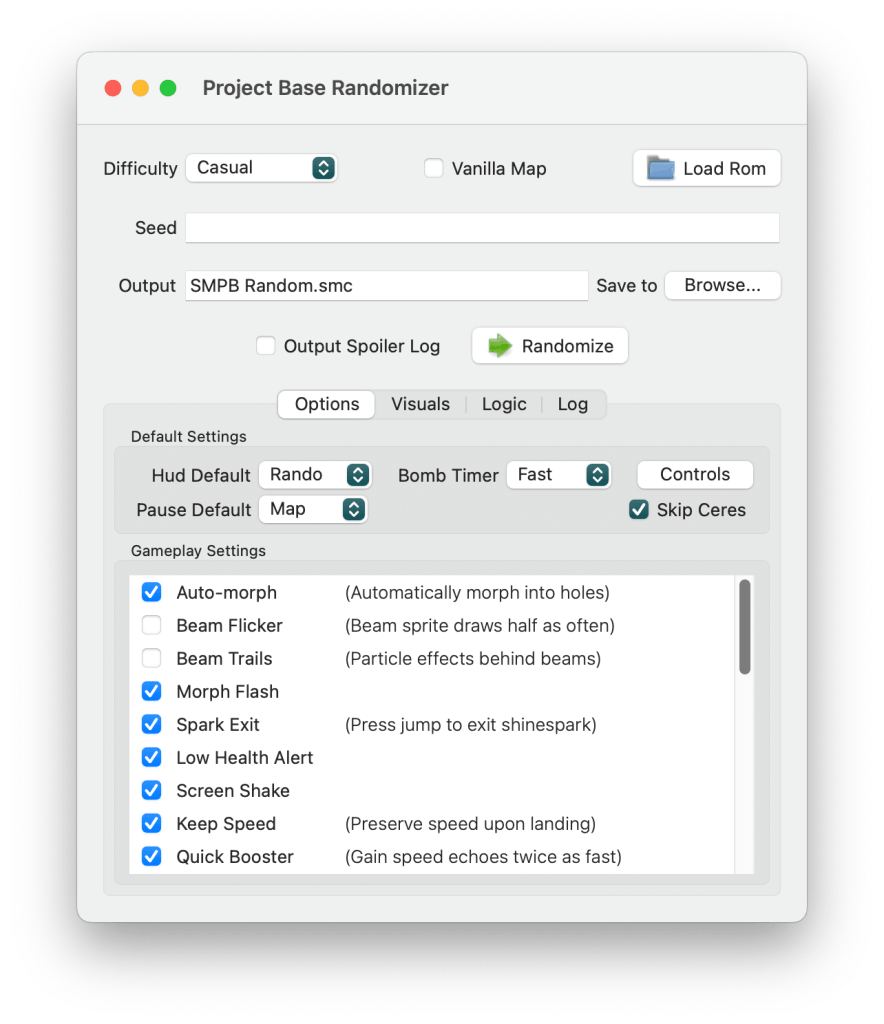

Randomizers are generally constructed on multiple levels. Whether those levels are distinct in the code depends on the implementation, but generally speaking you have The Interface, The randomization algorithm, and The low level game interaction. The interface can be constructed in all kinds of different ways depending on how the creator wants the user to interact with it. This could be a web app, a regular GUI program, or even a command line program. This part of the randomizer is pretty straightforward GUI programming. As an example, this is the interface for my Project Base randomizer:

Generally, randomizer interfaces have a way to load a rom to use, an input for a seed, and a difficulty selection. Beyond that, randomizers will vary according to the needs of the specific game. Some will have many options, some will be quite basic. The next layer of the program is the randomization algorithm itself. This may be directly integrated into the GUI programming, or it might be encapsulated as its own set of functions, maybe even its own object. The implementation will vary, but the randomization code itself doesn’t have anything to do with the GUI, so it can be considered a separate layer. The same interface could be used regardless of which algorithm is used for randomization. In the case of the Project Base randomizer, the randomization algorithm is a separate file, called with a simple function from the GUI:

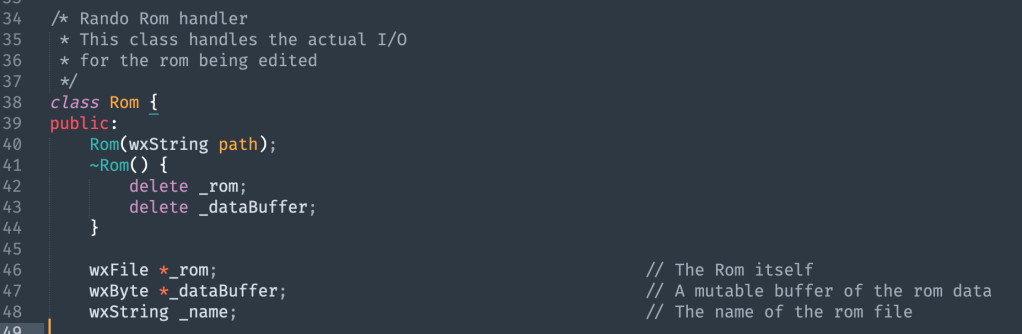

This calls a set of functions that randomize the items in a given rom. Currently it assumes that the rom is stored as a class member, ‘_rom’, but it could be encapsulated further by having to pass in a reference to _rom instead of it being part of the same class. Ultimately you could have logic be an object which asks the GUI object to pass the reference once the rom is loaded in. However I felt it was unnecessary in this case because the randomization is not as large and complex as it would be if it for example used a node based algorithm. Lastly, we have the final layer of the randomizer, which is the interaction with the rom itself. This is often tied directly into the randomization code, but if you want to encapsulate the program further then you might have a class and object for the rom, and the rom has its own methods for performing any kind of data access or manipulation. Either way, this layer is where the actual changes are made to the game. This might mean editing a file, or it might mean changing values at certain addresses in a rom, or changing actual game code itself, or it might even be entirely different depending on how the game is being interacted with. For our purposes, let’s assume that it means changing values stored at certain addresses in a rom. Finding the right addresses to change might require reverse engineering the game, or it might be as simple as checking a document depending on what rom hacking support the game has gotten over the years. Either way, I consider this layer distinct from the others as it doesn’t matter what the result of the randomization is, the program will still need to access and modify the underlying game code or files themselves. In the case of the Project Base randomizer, this layer is handled in its own class, and the rom object is what performs the rom access/modification operations. This is partly for the sake of encapsulation generally, but it is also because my randomizer need to perform a few different kinds of operations on the rom, and it’s helpful for them all to be in one place. The Project Base randomizer for example needs to be able to compress a palette into the rom for its palette randomization feature, and so the rom needs to be able to take a palette and compress it into the game data. Otherwise, it performs the expected operations of accessing and modifying bytes at specific addresses.

Do we even need an algorithm in the first place?

Okay, so you want to make a randomizer for a game, and you’ve got the interface and low level interaction sorted. Great! Now for the important part, the randomization itself. There are many, many different ways to tackle the problem of randomizing items in a video game, but I am going to go over a few of the common approaches. First though, let’s outline the problem itself.

What we need:

– A game

– A list of items in the game

– The location of the data representing each item in the game

What we want:

– To randomize the item list such that the game can still be completed

The last bit is important, we don’t just want to randomize the item order, we want to do so in such a way that you can still complete the game every single time. If we were to completely randomize the order of the items, then we will almost certainly end up placing items before items that are required to get the previous item. This is because items in these games act as keys, and ‘unlock’ different locations by allowing the player to visit them. This presents some problems that we will have to tackle.

Okay, so we know what we want to achieve, and we have the basic elements we need to do so. That means what we have left is to design a system that uses code to randomize the order of items without making the game unbeatable. This sounds fairly straightforward at first, but trust me, it will get messy pretty quickly. Let’s start by trying to come up with an approach, and then after I’ll get in to the common ones.

The first approach you might think of, is to start by completely randomizing the order of the items. This is very easy and fast to achieve, as you can put all the items into an array which corresponds to a list of locations, and then shuffle one of the lists. Now you have random items at each location.

However, we run into an issue right away, in that we don’t know whether the game is completable like this. We know the items are randomized, but we don’t know if that order allows a player to get from the start to the end without getting stuck. So, how do we solve this? We could design a system that tries to prove whether a given order is completable or not. This might be simple if the list of items is very small and the relationship between item locations is simple, maybe even linear. However as we scale this up to a more complex game, it will quickly become very difficult. How do you simulate the player picking up different items and getting to different locations? You would at the very least need to add a new attribute to the item list, some kind of ‘requirement’ attribute. However even if you simulate a player going through the item list, you now have a new problem. If you have to prove whether a player can complete the list or not, you now have to repeatedly randomize the list until it is proven to be completable. Now for a small list, this might not be a problem. Maybe the game is extremely open and there are countless possible ways to order the items that will work, and so having it check if it’s completable every time is trivial for a modern computer. But let’s assume the game is at least somewhat complex, with many different connections between locations, and a decent (let’s say, 20) number of items that each affect the traversal between items in the list. Proving that it’s possible is going to get very complicated and the likelihood that a completely random order will be completable gets statistically less and less likely. If we assume 20 items that each affect the progression (as in, we don’t count items that need to be placed but do not affect the progression), then randomly ordering them provides 20! (20 factorial, which is astronomically large) possibilities, most of which will not work. So at this point we’re basically just throwing a bunch of dice and hoping each time that we get a specific number. So, what if we were to build the proving mechanism into the randomization itself? Instead of trying a random order of items and then trying to see if it works, maybe we can incorporate the logic of proving completability directly into the way it chooses items. And with that, we’ve arrived at the need for an algorithm.

Now, truth be told, some games really can be randomized the way I described, by choosing a random order and proving that it’s possible to play through it. But that only works on very simple and/or open games, where most arrangements of items will work and it’s just a matter of avoiding the few permutations that don’t. But those aren’t the type that I’m discussing today. What interests me personally is the case where the arrangement of items has so many possible and impossible arrangements, that you need some kind of algorithm that determines the order programatically with elements that are randomized, rather than guessing.

Types of randomization algorithms

Okay so, we know we need some kind of algorithm to determine item locations, rather than just randomizing them and hoping for the best. There are two primary approaches to this problem, although I’m sure there are many more, and I’d love to hear about more of them.

Location lists

This is the name generally given to the approach which uses, as the name would suggest, a list of locations. Each location in this list has a path from the starting location, to the given location. This path represents the items and requirements to get from point A to point B. This representation can take many forms, but we’ll get back to that. For now, it’s just an abstract ‘path’ of requirements. The algorithm uses this list of locations to determine where it can place items by seeing if the ‘path’ is clear for any given location. If it is, then it is a candidate for an item. So the general idea is to place items in locations that are open, and then re-evaluate the list to open more locations with the placed item, until all the items are placed. Now, this itself can be done in different ways (forward fill vs back fill), but the idea is the same. Find what locations are open based on what items the hypothetical player has, and place an item, then re-evaluate the list. This is generally very fast, because there’s no real path finding happening. The path for each location is pre-made by the creator of the program and built into the location list. So as long as the evaluation of the list is fast, and the other aspects of the algorithm are fast, the entire thing should run in negligible time.

Node based maps

This category defines the type of approach which does not pre-compute the paths for each location. Instead, it treats the locations like nodes in a large map (or in more technical terms, a graph). The way decides on item locations then, is by manually searching the node map as if it were a player moving through the game from location to location. This method has many advantages, such as the ability to simulate movement from any given location, not just the pre-computed one. It also allows the level of complexity to increase without massively changing the locations themselves. For example you might decide to introduce a new kind of progression block, and instead of rewriting every location, you can simply add them as a new variable to evaluate as the algorithm finds a way through the map. However, this approach also comes with down sides. It is much more complex to design and program, and it is an order of magnitude slower than location lists. So for large games with hundreds of locations and dozens of items determining progression, even an efficiently designed algorithm might take seconds to run. If it is not efficient, it might take real world minutes to run a single time.

Node based randomizers are fascinating, and will be relevant to my potential new randomization method, but for today I want to talk more about location lists, because this is what the Project Base randomizer is based on. The decision to use a location list was made mostly for time, as there already existed a location list based randomizer of Super Metroid, and one of a previous version of Project Base, therefor much of the location logic (the pre-computed paths that is) could be carried over into my new system.

The randomization algorithm

So, we’ve picked an approach for the algorithm, but how do we actually implement it? This is an interesting problem, because it can be approached in many different ways, depending on the creator and the language and framework they chose to use. For starters, what exactly are the locations themselves? Are they objects, structs, primitives, strings, etc.? I think in most cases, they will be treated as structs or objects, as they have to hold a few different pieces of information. They need to have the pre-computed path itself, but depending on how the algorithm is designed, they might also need to hold the value of the item being placed there, or maybe whether the location is available, etc. This leads us to the first big question in my opinion, which is, what is the pre-computed path? How is it represented in code? Well, I’ll start with two examples that I’ve seen. The first is to represent the path as a nested set of function calls. Ie. a given location might have a function to check if area A can be traversed, and area A might require area A1 and A2 to be traversable, and area A1 might need items X,Y,Z to be traversable. So it might look like canTraverseAreaA() -> canTraverseAreaA2() && canTraverseAreaA1() -> hasItemX() && hasItemY() && hasItemZ(). As you can imagine, this can get messy very quickly (for example, you can’t tell from looking at the main function, what other functions are required, you have to follow the function to find out), however it has an advantage in that functions can perform any kind of operation, so you can have extremely different requirements that all get processed together in the same function call. The other method is to represent the path as a string. ie. “itemX && itemY && itemZ” which is then parsed and processed. There are more options, as we will see when we get to my algorithm, but those are two of the basic options.

Along with locations, we need some kind of structure that represents the player, so that we can keep track of what items have been placed (and therefor acquired by the hypothetical player), and so that we can check if a given path is traversable. So for that let’s just say it’s an object, and this object can hold items in some form. We also need some representation of the items themselves. This can be as objects, or maybe primitives depending on how the algorithm works. They can be stored in different data structures as well, but let’s say for now that we store the items in a dictionary, which has information on the value of the item and the location in the rom of the value.

So we have a list of locations that take the form of some kind of structure containing likely a string or a function pointer. Next we need to put those in some kind of data structure that we can look through and manipulate the contents. For location lists, this is usually a vector of some kind (or List, or ArrayList, etc.). However since the locations are all unique, you might use a set instead, or maybe a dictionary depending on how the algorithm operates. Regardless, we now have a list of locations, and we want to somehow determine what items to place where.

Step one seems obvious, check what locations have paths that are available right away. But what do you do with the locations that are available? Let’s say that you take them out of the main array, and put them in a new array (this is not always how it’s done, but it means you don’t have to re-traverse those locations in the list next time). Next maybe you choose a random location from the set of available locations, and you assign it an item at random. Okay, now that item presumably opens up more locations, so let’s re-evaluate the location list and do the same until we run out of items. Except wait a minute, what if it’s an item that doesn’t happen to open up any locations that are connected to the first ones? Remember, each location path has all the items and requirements between the starting location and the current location, so it’s possible that an item will open part of a path but not all of it for any given location. Since these locations are not linked together the way a node map is, we have to rely on the pre-computed paths having all the possible requirements for the entire path. That’s the only way the location list prevents locations opening that aren’t accessible yet. So, we need a way to know which items will create actual progression, and which ones will open parts of paths but no full paths. On top of this, I’ll add another issue. What if you choose an item that opens a path but after that the lowest number of items to open a new path is greater than one?

These are both tricky issues to solve, and there are many ways to solve them. For our purposes however, let’s use a simple solution to each of them. For the first, we just need a way to determine whether an item will grant progression or not. So let’s start by defining what progression is. Progression means there are locations that are now available, which were not available before. So, logically, if you hypothetically assign an item, and the list of available locations goes up, then we know it’s progression, and if it does not go up, we know it won’t help. Therefore, we just need a way to simulate adding an item, so we can tell if it grants progression or not. There are once again many different ways to do this, but for the sake of brevity, let’s choose a really simple one. You give the player object an item, re-evaluate the location list, and keep track of whether any locations are now fully open. If so, we say this item is progression, take it away from the player object, and put it into an array of items that are progression capable. Then we do the same thing for each possible item, and at the end we have a list that we can randomly pull from, which will for sure have a progression item. This method may seem slow and doesn’t scale well, because it is slow and doesn’t scale. But for now, it’s good enough. The real tricky thing, is when you open a path that leads to a location where the only way to make progression is with multiple items. There are a few ways to handle this. For example, you could simply re-try the whole algorithm if this happens, until you get a selection that does not force that requirement. You could also change the algorithm to something referred to as ‘backfill’ which avoids the problem altogether, but for our purposes we want to find the simple solution, so let’s assume we re-try the algorithm in this case.

My randomization algorithm

So, my implementation is similar in broad strokes to what I described above. It uses pre-computed paths, and it places items moving forwards from no items to all items. However the methodology is quite different. So to start, let’s talk about the pre-computed paths.

Pre-computed paths represented as expression trees

To avoid some of the issues with using nested function pointers, I decided to use strings to represent paths. This way, I was able to have the items be represented as bits that are inserted into the strings, making it easier to write large paths. But this does come with a cost, having to parse the string to calculate whether the location is open or not. To solve this, I use expression trees. Basically, a ‘location’ is a struct that takes in a string representing the full path, and then the constructor converts the string into a tree structure that represents the boolean logic.

An expression tree is a binary tree that represents an expression. Each node in the tree represents an operator or a bit. The bit being an item or other requirement like a trick. So when the location struct is created, it creates an expression tree out of the string expression, and stores the top node in the struct. The reason for this expression tree, is that it is very fast to evaluate. We don’t need to parse anything to read the expression, and we don’t need bespoke functions for each requirement. We just need a function that can read an expression tree quickly. This also allows us to short circuit the expression where possible, saving time. This kind of pre-computation is a big theme in my algorithm, it will come up again later. An expression tree is useful, but it doesn’t change the core algorithm, it just changes the process of determining location logic. The next part is where this algorithm diverges from the norm.

Item placement, requirements, and pre-computation

Item placement is the bulk of the randomization algorithm. How the program actually decides what item to give and where. The beginning is similar, we want to move the open locations into their own array by iterating through the location vector and checking each one to see if it is open. After this however, things start to differ. Instead of giving a hypothetical item to see if it makes progression, we need to change perspective a little and ask the question, what information do we have? The thing is, when creating the expression tree, we already have all the information we need about items to determine item placement, from the bits involved in the location logic. Essentially, if we have a list of locations, and the locations have bits that determine items required, then for any given set of locations, we already have a list of items that make progression, we just need to extract it somehow.

This system is therefore designed around ‘requirements’. The basic idea is that when we create an expression tree out of an expression, we know what items will make progression already, because they are the requirements in the expression. So instead of creating a list of progression items, we just need to look at the requirements of locations that are not yet accessible, as those are the items that are needed to make progression. The way this is implemented currently, is that when making the location struct, we also build a set of items that represent the requirements in a given expression. This may seem odd, as you could always find a way to translate an item requirement into an item, and then you don’t need a separate set. However, we will see why this is needed in a minute. With a set of items for each location, we now have a way to know what items are possibly needed for making progression. Therefore, we can take all of the sets of items from unavailable locations, and sort them by how many items they need for making progress, and what items those are. This way we can find what the smallest size of item requirements is at any given time, and apply all the items from that set. This allows for situations where multiple items are needed for progression, not just one. This also allows us to weigh the items themselves to make it more or less likely for powerful items to show up early on.

Now, a flaw you might be thinking of with this system comes in the form of OR statements. If you make a set of all items from an expression, but some items are in the form of OR statements, then when deciding on items, you have both instead of one or the other. This is where the pre-computation comes in again, and why we create the set of items instead of translating the bits into items. What we can do, is process the OR statement in advance, by making the random choice of item between any two items, when building the set itself. This means we are still choosing a random item from the OR statement to give, we are just doing it before we look at the location when processing the logic later on. There is a lot more nuance to this, but that’s the general idea. As a result the flow of information basically looks like this:

Item bits -> String expression -> Expression tree + item set -> Requirement set -> Placed items

The process itself

This whole process is essentially a five step operation.

- Initialize the locations and item pool, and build the expression trees and sets for each location

- Find all available locations with the current equipment and put them into a new vector. At the same time, find the lowest requirement size for the next step, as well as erasing the last item placed from the requirements set of each location

- Build a list of all the sets with the minimum requirement size, then pull a random set from that list to use for items

- Use the requirement set to distribute requirements as items in random locations across the currently available locations

- Distribute the remaining non progression items based on their weight

There is of course a lot more that goes into the code to run this, especially dealing with the hash sets and whatnot, but hopefully that gives the basic idea of the algorithm.

Future randomization algorithms

So although I like the design of the algorithm used in the current Project Base randomizer, I also have a vision for a new type of algorithm that could combine the positives of the different approaches. I’m not going to go over it in detail here, but the idea is essentially that the program takes as input not just a rom, but also a map of the game. This map would be processed by the program into a node based map of locations, requirements, and items. From this node based map, the program would then create a system of pre-computed paths by grouping nodes and groups of nodes. This would only need to be done once, or if the user wants to change the starting location of the player. Once it has the network of paths, it could then compute what locations are open at any given time much much faster than traditional node systems, and negate the need for backtracking and path finding inherent to that approach. At the same time, it would be dynamic, able to change the starting location, or add new variables easily.